The excellent Sydney history book Shady Acres explains the intriguing circumstances in which Sydney’s Croydon station came into the world.

Written by historian Lesley Muir, Shady Acres delves into the links between property development and the construction of new 19th century public transport.

To this extent, the book notes that Sydney’s Croydon station was constructed in the 1870s despite the fact it was just “half a mile” from nearby Ashfield station and at the time there were very few local residents who would use it.

This situation begged the question as to why the station was constructed at all.

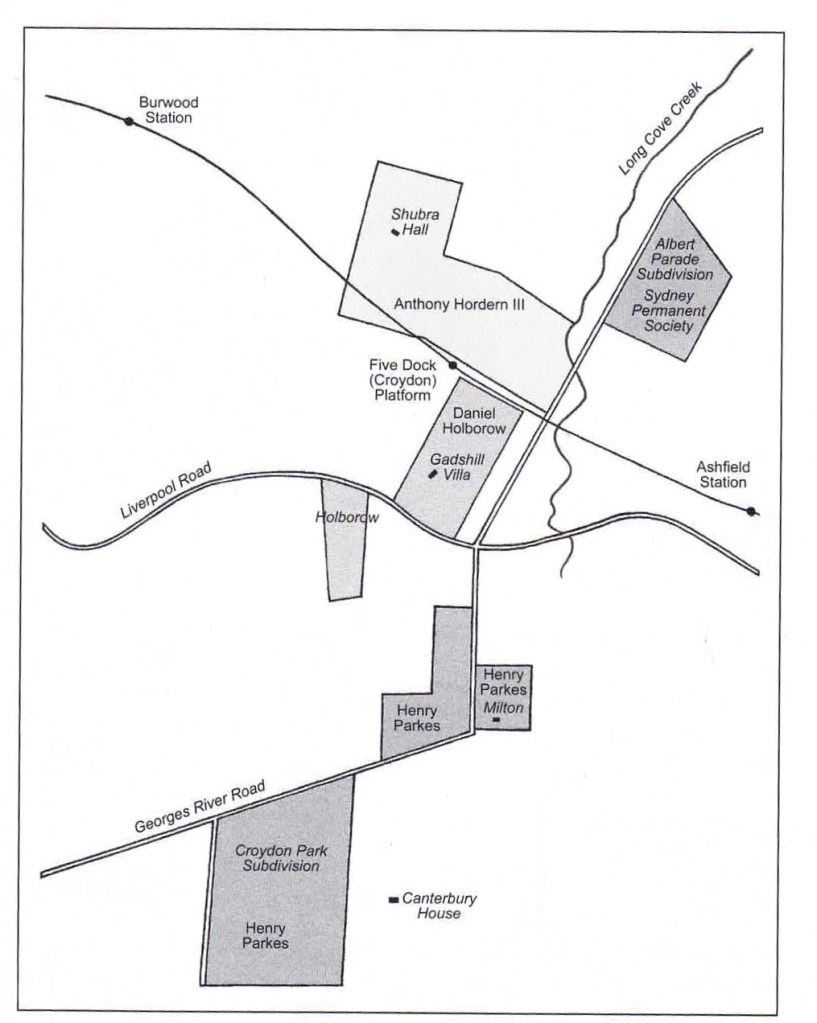

Well, the answer to that question will probably never be known, but Shady Acres provides a useful clue by explaining that then Premier Henry Parkes and his political supporter (and mayor of Ashfield) Daniel Holborow had both purchased land in the area.

In fact, a few weeks after Holborrow assumed the Ashfield mayoralty, Ashfield Council was petitioning for the station’s construction.

As a result of the station’s construction, Parkes was able to subdivide his land for a “handsome profit”. The station was even re-named from Five Dock to Croydon, to reflect the name of Parkes’ newly subdivided estate of Croydon Park.

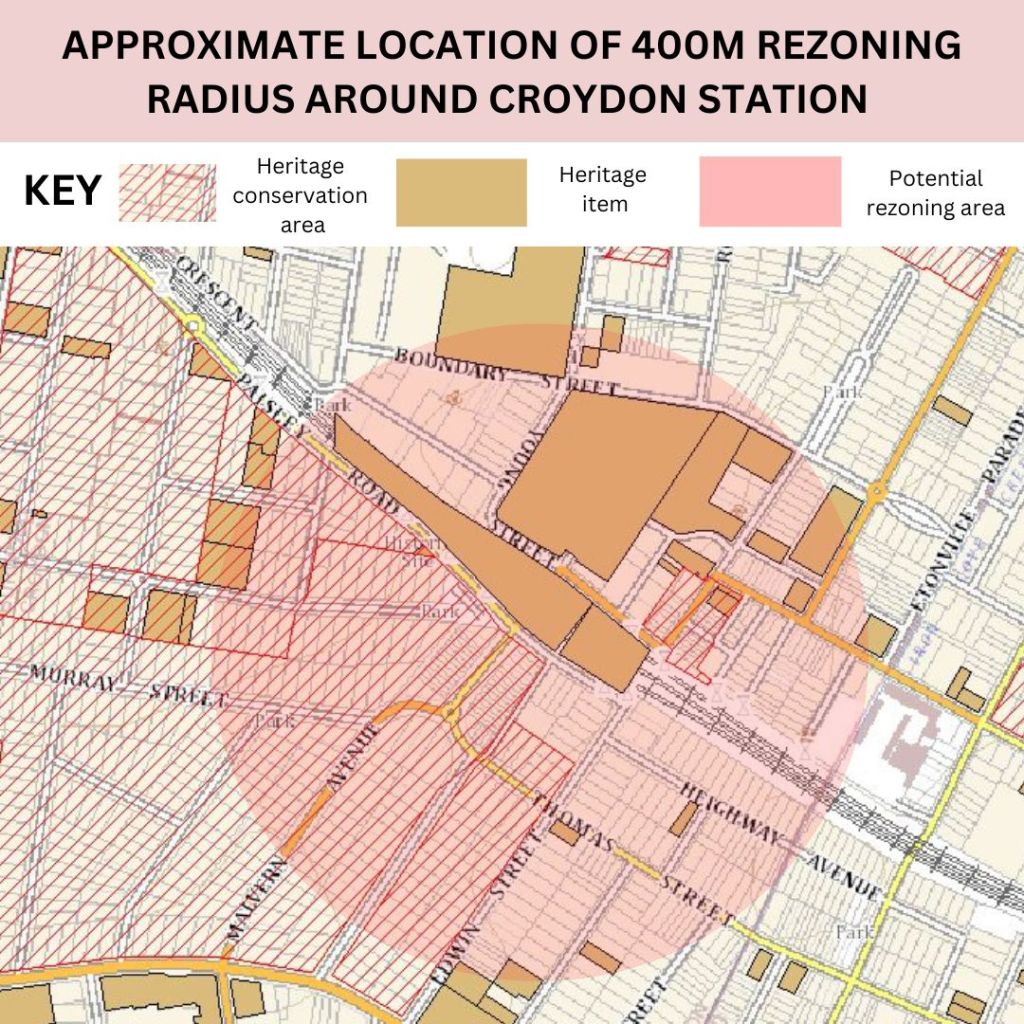

The link between Croydon station and property development once again emerged before Christmas, when the area was named as one of 31 Sydney precincts to be subject to the NSW Government’s Transport Oriented Development program.

This means that, on 1 April 2024, an area 400m around the station will be rezoned for six-storey residential unit blocks, including in existing heritage conservation areas.

This will in effect destroy the same low density subdivisions ushered into the world by the station’s construction, which for the past four decades have been subject to statutory heritage protections.

Of all the station precincts subject to the government’s announcement, Croydon arguably has the largest heritage precinct to be impacted by the 400m radius.

Sydney Insider went for a walk around Croydon, to see the affected area.

Before describing the homes which could be demolished, it’s probably worth first understanding the way that Croydon was first planned.

Be notified of every new Sydney Insider blog post by email

In the years just before Croydon was first subdivided for residential housing, there was significant media and government attention on the alleged horrors of the “slums” which existed in inner-Sydney. Between 1900 and 1909, there were some 2,590 stories in the Sydney Morning Herald and Daily Telegraph focussed on the issue of “Sydney slums”. That means there was a story on “slums” in the daily press two out of every three days.

In 1906 a new Local Government Act was passed in NSW, which provided local councils with the power to lay down strict conditions about standards for both planning and building in all new developments.

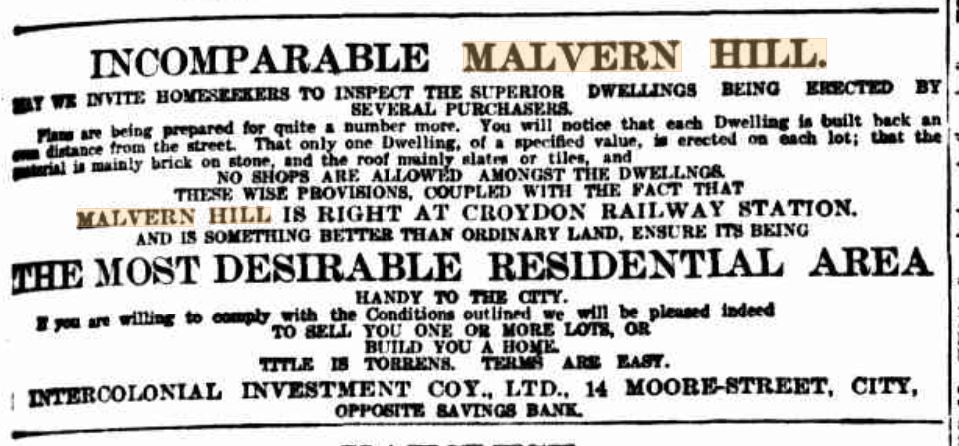

Ashfield and Burwood Council worked together to use these powers to create a model suburb for the new subdivided area south of Croydon station, which was marketed by the name Malvern Hill. The suburb was based on the emerging belief that homes should be well-built, surrounded by fresh air and light and well-separated from industry.

The councils approved the subdivision plan in March 1909, including requiring that streets were at least 20m wide and the development company pay for all drainage. In addition, building covenants were placed on the titles of the newly-subdivided blocks.

At a public square at Croydon, Burwood Council has helpfully installed plaques of the original subdivision advertisements, which list the detail of the covenants.

These include that new homes are worth 400 or 500 pounds or more, that the homes are constructed of “brick or homes or both”, that roofs are mainly “slate, tile or shingles”, that there cannot be more than one dwelling on each lot (meaning terraces were not allowed) and that each house is at least 6m from the street.

In addition, no “hotels, diaries or shops” could be constructed on the residential land.

These controls have created the southern part of today’s Croydon, with streets lined with substantial Federation homes, of Queen Anne or Arts and Crafts styles, many with generous front or corner balconies, hedges and brick fences.

To market the suburb, the original subdivision sellers promoted the location as “the highest land between Sydney and Strathfield”.

This gave the Croydon area a Scottish high country theme, which exists to this day via the Scottish accessories shop in the main street, along with the presence of the Presbyterian Ladies College and Uniting Church in the suburb.

In 1981, the area was recognised by the National Trust and in 1986, Burwood Council gave the original Malvern Hill estate statutory heritage protection. This means Croydon has had heritage protection for at least 35 years (at some stage Ashfield Council also protected its portion of the Malvern Hill estate).

The suburb’s grand homes also now come with an even grander price tag, with the more prestigious heritage houses likely to be worth at least $3.5-4m. Across the entire suburb, the average house price is around $2.3m, an increase of 23% in the past year.

However, the suburb’s original planning philosophy – that homes should be located on their own block of land surrounded by fresh air and natural light – has gone from being considered an enlightened and positive approach in the early 20th century to a major problem in the first quarter of the 21st century.

This is because these same homes are now seen to be blocking the development of smaller homes which could help solve what is perceived as today’s primary planning problem – housing affordability.

As a result, Croydon’s heritage protections would appear to mean little in the face of the expected NSW Government rezonings, which will involve the redevelopment of individual blocks of land for unit blocks for up to six storeys in height.

The NSW Government has indicated there will be “substantial change” in these heritage areas, and has indicated the presence of a heritage planning overlay will not mean these areas will be spared from redevelopment.

What’s more, the original catalyst for the dubious establishment of the suburb – public transport – is once again being used as the trigger for Croydon’s development.

We will find out, on or before 1 April 2024, what these rezonings mean for Croydon and the other 30 suburbs on the Transit Oriented Development program list.

That’s the day the government is intending to make the rezoning, after consultation only with relevant local councils.

In the meantime, Sydney has the opportunity to consider whether it thinks it is a good idea – after considering the current housing affordability issues – to undo more than 100 years’ worth of planning and redevelop Croydon.

What do you think?

Discover more from Changing Sydney

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.