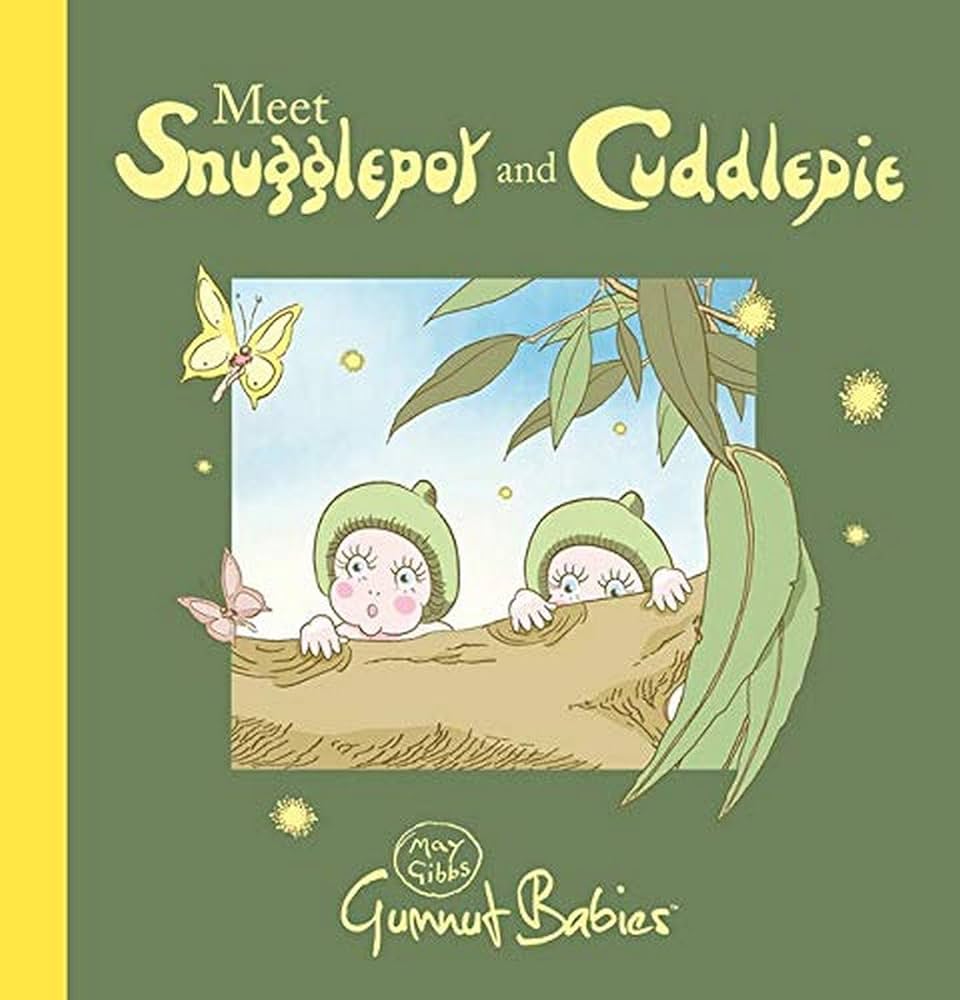

Despite it being more than 70 years since her last book was published, the works of Sydney’s children’s author and illustrator May Gibbs are still held in great affection across Australia and the world.

Characters such as Snugglepot and Cuddlepie, Bib and Bub and the Big Bad Banksia Man are etched into the national memory, in part because they bring traditional Australian flora to life in a fun and humorous way.

Less well-known, however, are the extraordinary actions of North Sydney Council and locals to successfully preserve her home and grounds as a public museum, despite indifference (and sometimes outright hostility) to the cause from the NSW and Australian Governments.

Home sale and development proposal

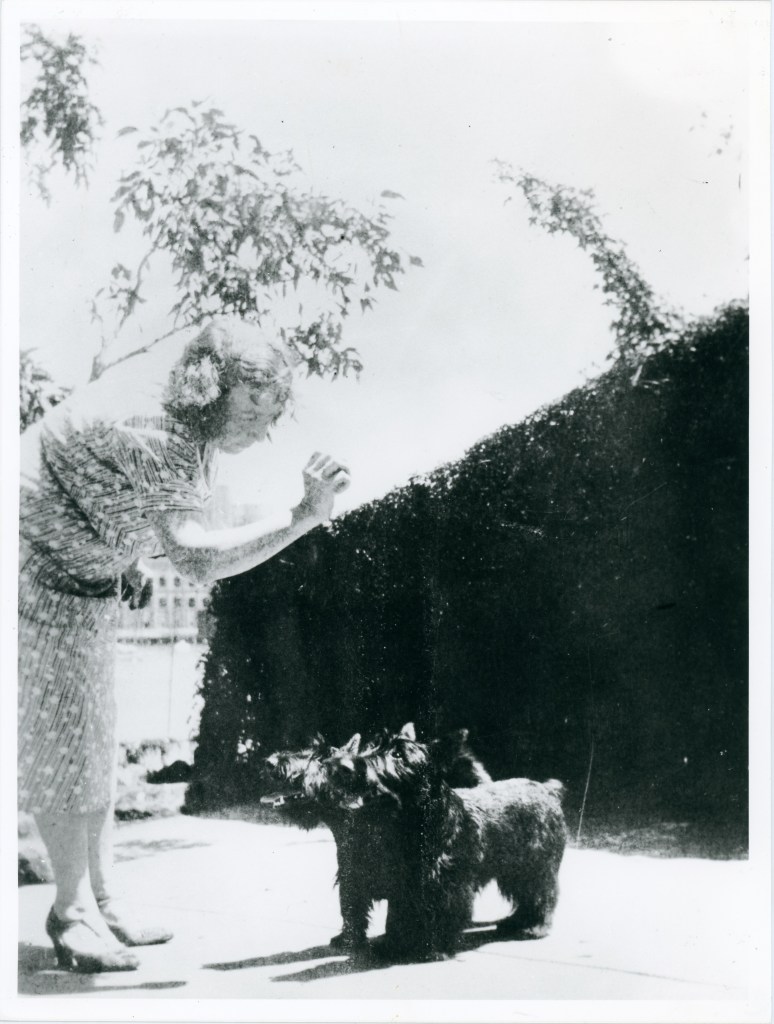

The story begins in 1969, when Gibbs passed away at the age of 93. Without any children of her own, Gibbs gave her Neutral Bay waterside home – known as Nutcote – to international children’s aid agency UNICEF.

However, this was not just any home – Nutcote contained gardens with native plants, birds and animals, which formed the inspiration of Gibbs’ work.

The sloping property was divided into four sections – a garage facing the street, a top garden, a home (which was constructed in 1925) and then a bottom garden running to the harbour’s edge.

In 1970, the home was sold by UNICEF and then purchased, and lived-in, by a married couple.

However, in 1987 news broke that a developer was working with the owners to develop the garage and part of the top garden into townhouses, while retaining the home for private use. In August 1987, a NSW Government Commission of Inquiry, and the NSW Heritage Council, supported this application.

There was a view in the NSW Government that the site was suitable for private property development, but its location in a narrow street meant it was not suitable to be a museum.

However, for a growing band of May Gibbs’ enthusiasts in northern Sydney and right across Australia, this wasn’t an acceptable outcome.

It would mean much of the home’s original leafy surroundings (such a critical part of the May Gibbs story) would be lost, while the home itself would be modernised and remain off-limits.

“It will be a terrible loss to the Australian heritage if May Gibbs’ house and garden is altered,” said Marion Shand, a second cousin of May Gibbs. “The house and studio, where May Gibbs worked, is full of atmosphere.”

The fightback begins

A foundation and campaign was launched to buy the property – a very tall order given the estimated sale price of $1.5m (around $4.3m in today’s dollars).

In January 1988, this campaign received a boost when North Sydney Council voted to resume the site, but on the condition that the NSW and Australian Governments each contribute one third of the cost, with the council and newly-formed May Gibbs Foundation the other third.

However, if the council hoped this would spark action from other levels of government, it was wrong.

The Australian Government went missing in action and, although he was willing to meet with the council, then NSW Liberal Premier Nick Greiner also gave a flat no.

It probably didn’t help that, at the time, either North Sydney mayor Ted Mack or his successor Robyn Read held the State seat of North Shore as independents, taking political territory traditionally held by the Liberals. Meanwhile, the home was also located in a Federal seat the ALP (then in government in Canberra) would never have a hope of winning. At a time when political allies were needed, none were to be found.

“The death knell sounds”

Despondent at the lack of support, North Sydney Council in May 1989 decided to withdraw the resumption threat, and the home went on the market soon after. The SMH reported that “the death knell sounds for Nutcote”.

However, at a time when it seems all hope was lost, an unexpected event came to the rescue.

In mid-1989, Sydney began to experience a severe property market downturn – in part from a delayed impact from the 1987 Black Monday sharemarket crash. This market downturn affected prized waterfront properties, such as Nutcote, more than most.

As this downturn began to grip, Nutcote was passed-in at auction in August 1989 and it was still on the market by November 1989.

In this period, North Sydney Council subtly moved from being the property owner’s enemy, to being in a strong position as one of the few suitors in the market.

Nutcote is secured

In January 1990, in a major breakthrough, the council voted to have the property valued and then negotiate a sale with the owners. In February 1990, the council and site owners agreed on a sale price of $2.86m and Nutcote became safe and secure, in the hands of a public authority.

However, the council then needed to begin a significant fund-raising campaign, to try to limit its actual exposure to around $600,000.

Many locals turned on the then State Liberal Government for its failure to help with this cause. Perhaps feeling uncomfortable that his party was finding itself on the wrong side of history, the new local State MP Phillip Smiles in 1991 lashed out and accused the council of “blackmailing” the government.

In May 1994, some thirty years ago today, the museum finally opened, and remains open to this day.

Despite the fact the museum is on a narrow street, it is more popular than ever for people using the Bondi to Manly walk or catching the ferry to one of two nearby stops. Visitors can wander through the home and gardens, as May Gibbs would have experienced them.

This includes being able to go on a tour of the compact 1920s home, with Gibbs’ studio set up as it would have been during her career.

The battle to save Nutcote is a story about passionate local interests working against the odds to save a national icon, and the unexpected benefits to the campaign which flowed from a global stock market crash.

Discover more from Changing Sydney

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.