Planning, almost always, is about the future.

Where do we put the new homes which cater for a growing and changing population?

How do we place people close to employment?

How do we preserve biodiversity and the environment?

Currently, the future of the NSW planning system itself is under scrutiny.

There is bi-partisan support for a re-write of NSW’s planning legislation, in part to speed-up housing supply.

However, in looking to the future, it’s important to acknowledge there are lessons in the past.

In particular, what were the key events which influenced the planning system we currently have? And are these events still relevant, or obsolete, today?

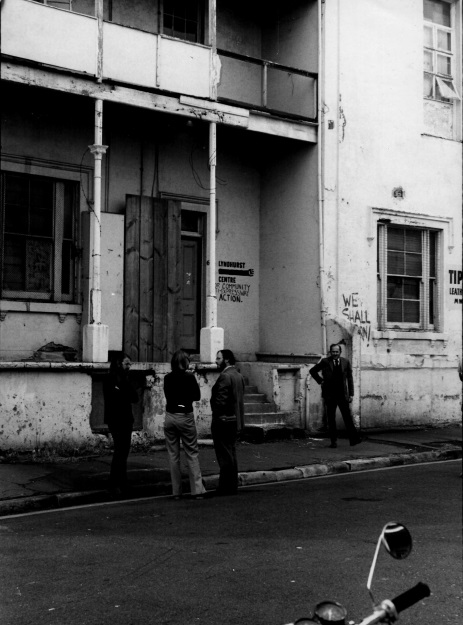

To this extent, I’ve spent the past decade researching the legacy of the extraordinary 1970s urban warfare which enveloped Victoria St and Woolloomooloo, in Sydney’s inner east.

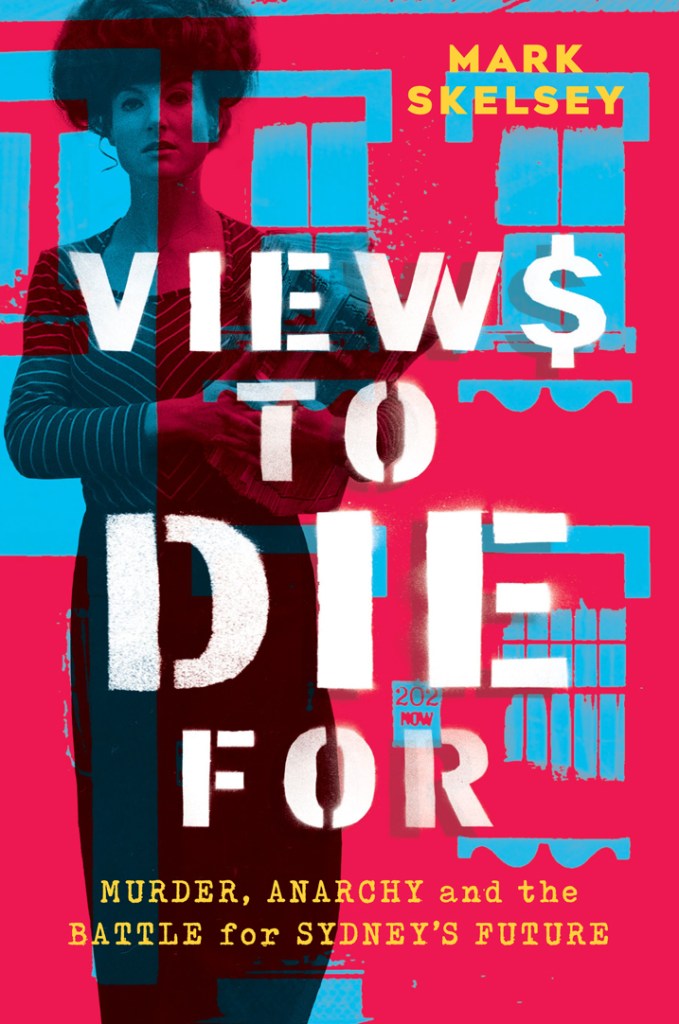

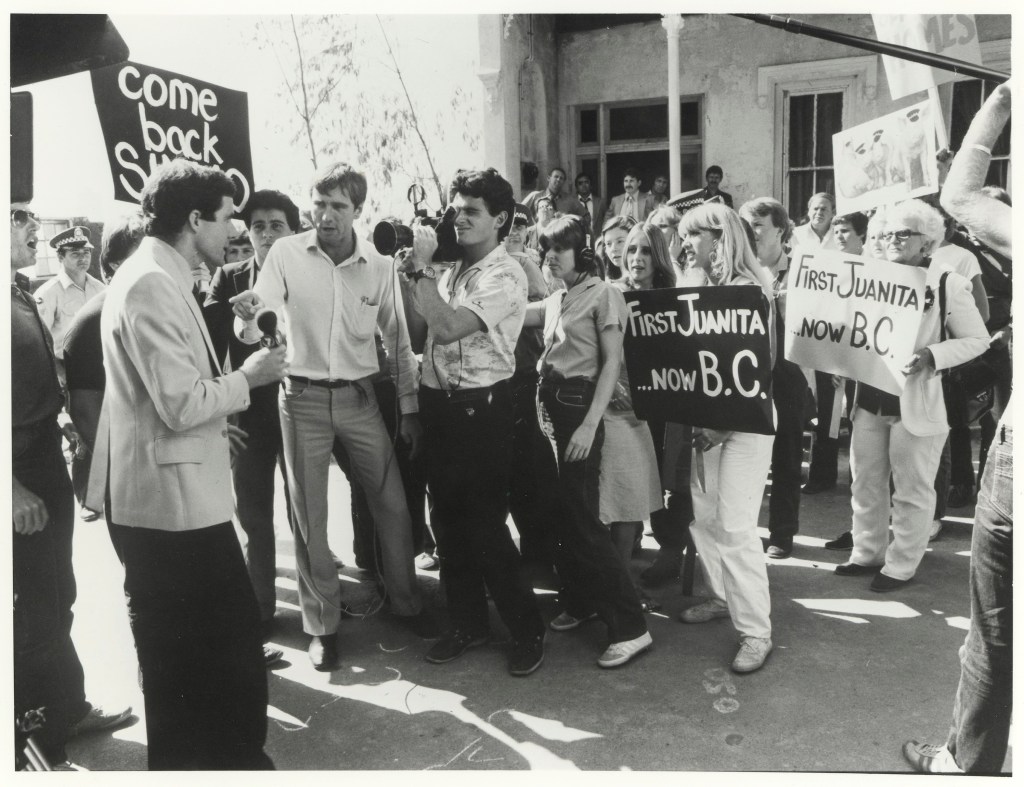

I’ve published a book, Views To Die For, which has been timed with the 50th anniversary of the murder of Kings Cross publisher Juanita Nielsen (who played a key role in this warfare).

PURCHASE VIEWS TO DIE FOR AT THIS LINK

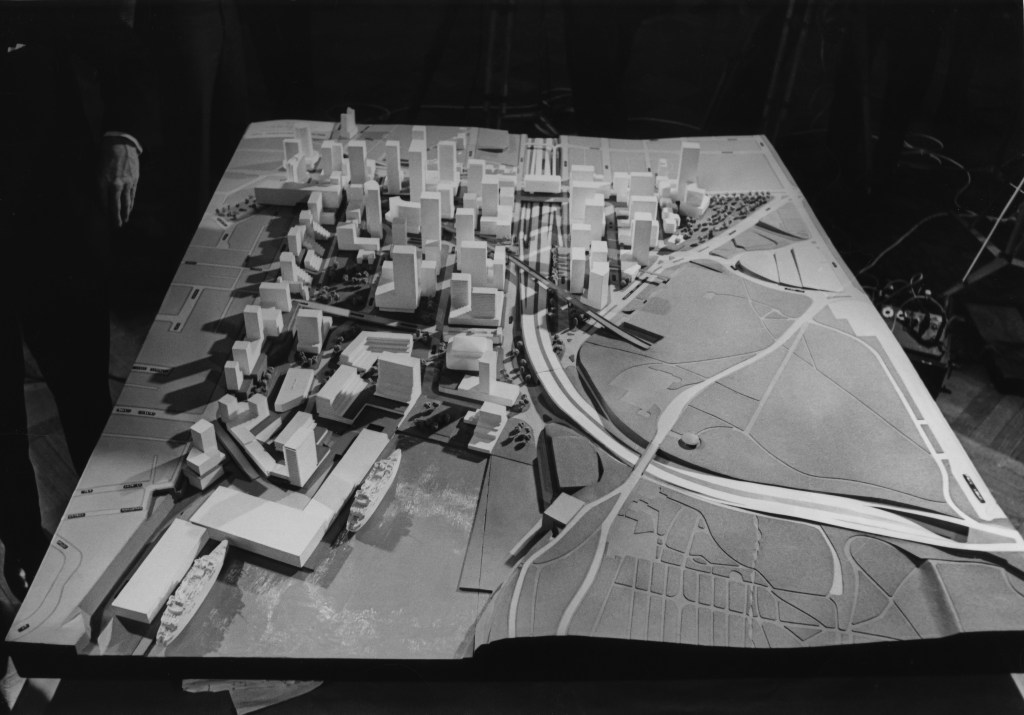

Views To Die For looks at the back-room development of a flawed 1969 NSW Government scheme which proposed to turn the tiny and low-scale suburb of Woolloomooloo into an extension of the Sydney Central Business District.

In creating this scheme, government bureaucrats provided secret background briefings to lure developers to the area, causing property values to boom, but at the same time failed to undertake the required consultation and planning within government to ensure future growth could be supported by transport and other infrastructure.

This caused great frustration for developers, embarrassment for government and an environment rich in conflict.

This scheme included the western side of Victoria St, today located in the suburb of Potts Point (but bizarrely not the eastern side of Victoria St).

Views To Die For then covers the bitter urban warfare which took place in Victoria St during 1973-75, after developer Frank Theeman tried to implement the Woolloomooloo scheme.

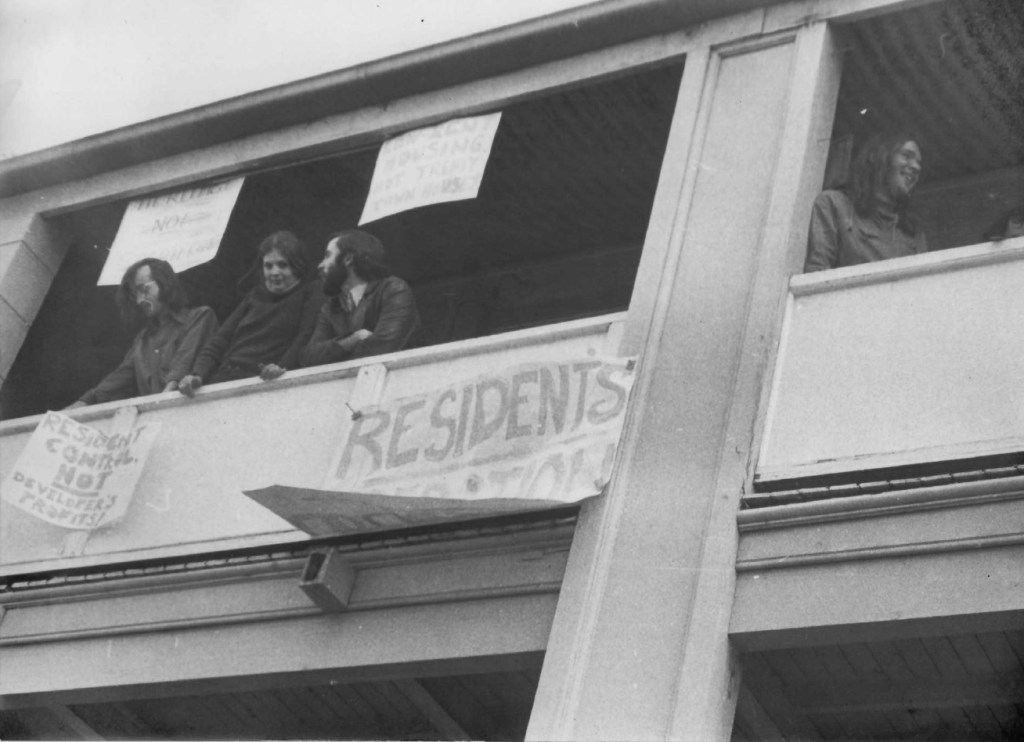

Mysterious security personnel brandishing pick handles appeared at Theeman’s site to evict and intimidate low-income tenants and, it is suspected, vandalise historic terrace buildings. “The shadows are pretty thick in Victoria St these days,” a newspaper reported.

Soon after, a squatters’ commune – led by Sydney anarchists – was formed in an attempt to resist the development and protect the buildings and affordable housing.

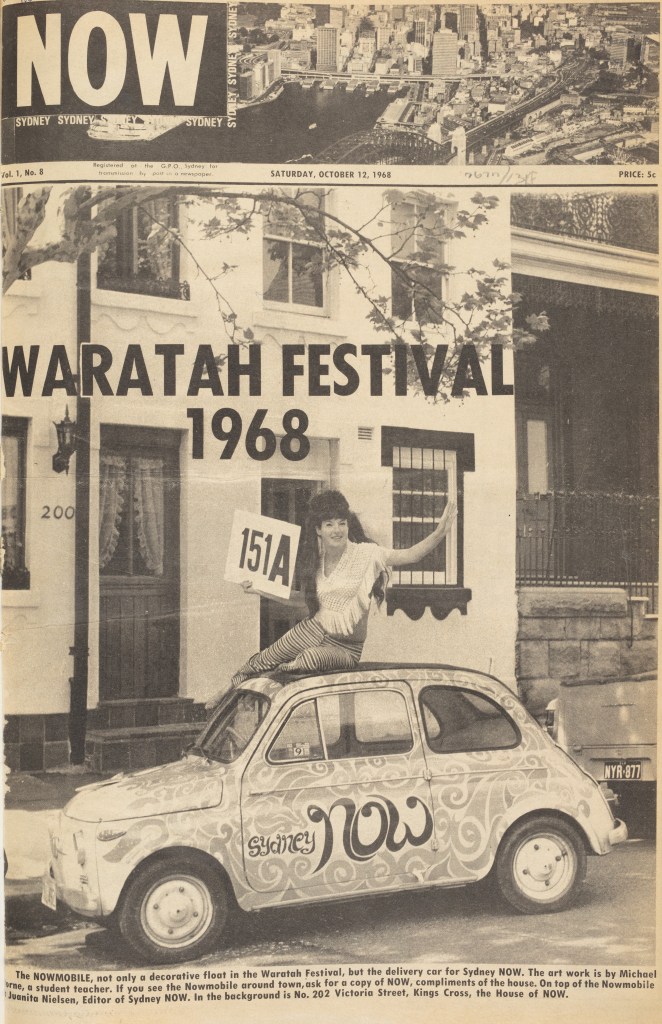

In the aftermath of the violent eviction of the squatters in January 1974, Nielsen used her newspaper NOW to take up the cause against Theeman’s development and to identify and raise concerns about development issues in other inner-Sydney suburbs.

Nielsen disappeared on 4 July, 1975, and her body has never been found, nor has anyone been charged with her murder.

Views To Die For doesn’t try to solve the Nielsen murder mystery.

Many others have tried, and failed, to do this.

But it does find that the Woolloomooloo and Victoria St planning wars, and Nielsen’s death, were a turning point in Sydney’s history, sparking a wide range of town planning and public policy reforms, culminating in the new planning and heritage legislation in the late 1970s.

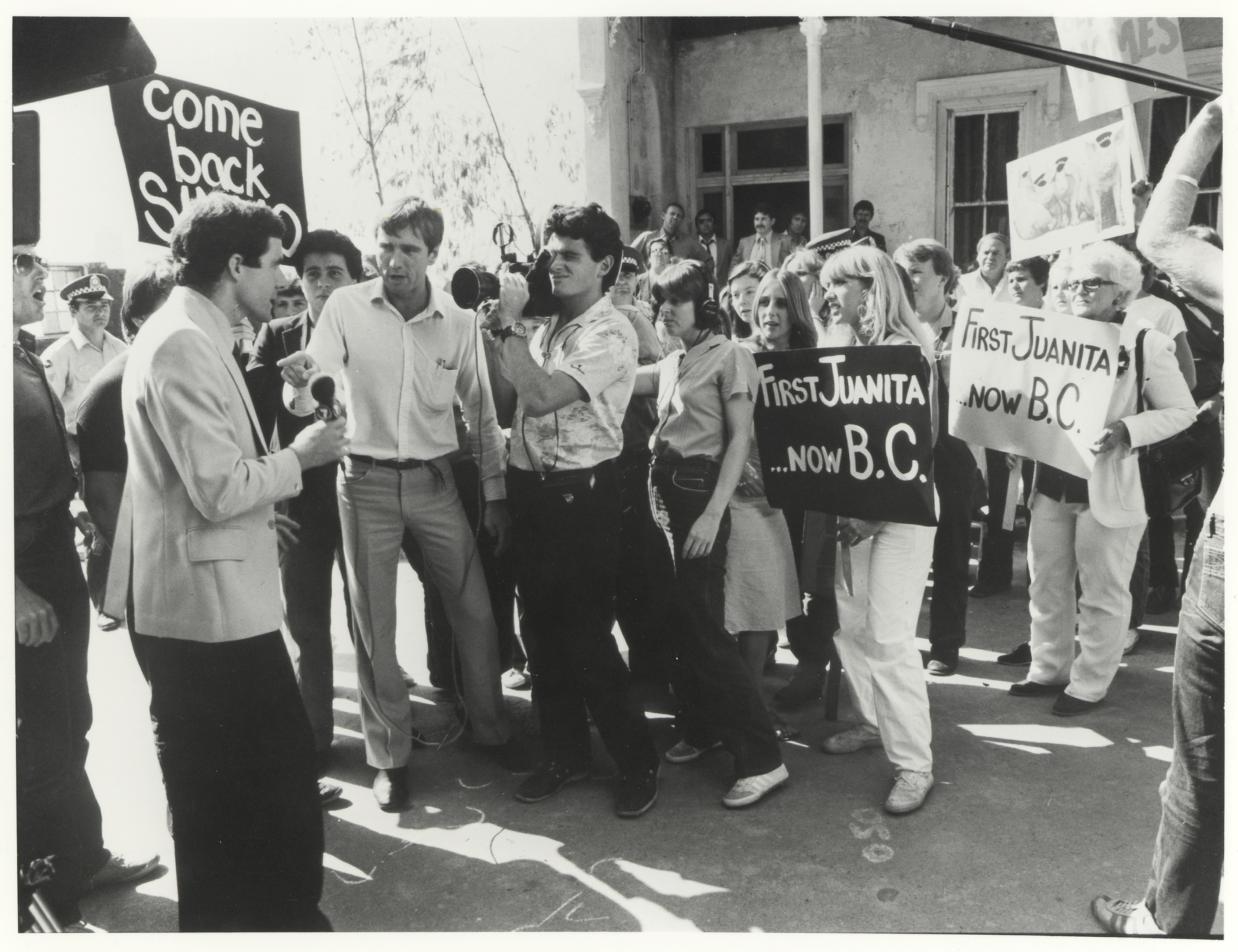

NSW’s main developer lobby group, in 1974, cited Victoria St’s well-publicised street violence as a reason to enter talks with resident action groups and unions to find new ways to resolve planning conflict.

Developers supported the preservation of historic areas and improved notification of planning schemes.

In a similar vein, the secrecy involved in development of the 1969 Woolloomooloo scheme was cited, by the Planning Minister of the day, as a reason to dramatically increase transparency and public participation in major planning decisions.

The proposed demolition of the Victoria St terraces helped spark reforms allowing authorities to be able to preserve entire precincts, rather than individual buildings, and to be able to use innovative air-space transfers as a conservation tool.

The now commonplace concept of mixed tenure developments – containing both market-priced and affordable housing – also surfaced in Victoria St as a proposed compromise to lift union green bans on the development site.

In addition, the final built-form on the Victoria St site was an early example of heritage retention (historic 19th century terraces) and new housing (ten-storey unit blocks) being delivered on the same site – another compromise flowing from the green bans.

Meanwhile, Nielsen’s 1975 murder led to, in the 1980s, a negative portrayal of developers in a series of movies.

Around the same time, there was a surge in resident action groups fighting development in Sydney, perhaps linked to new public participation laws.

This made the environment for developing land much harder than it otherwise would have been.

The Victoria St squat was also instrumental in inspiring later protests and efforts which resulted in the creation of new women’s shelters in Glebe and the dismantling of a proposed network of inner-Sydney freeways through older suburbs.

The changes brought about from the Woolloomooloo and Victoria St wars are now the subject of fierce and heated debate.

Is it possible to retain heritage and allow growth? Is too much weight given to public participation in planning?

Are attempts to preserve and deliver new affordable housing a distraction from, or even an impediment to, the alleged main game of delivering new market-priced housing?

Has the increased planning regulation of the past 40-50 years simply proven a hand-brake on housing supply and affordability?

However, in weighing up our future, we need to consider the lessons of the past.

This includes how secret planning can lead to disastrous outcomes, how it may be possible to deliver heritage and housing together and the need to consider the rights of vulnerable residents as Sydney grows and changes.

About the author

Mark Skelsey is a Sydney-based writer, and communications consultant, with a strong interest in urban affairs issues. He is the editor of this blog, Changing Sydney.

Mark is a former State Political Reporter, and Urban Affairs Editor, with the Daily Telegraph, and a former Media Manager at the NSW Department of Planning. Mark has a Masters in Environmental Law from the University of Sydney.

The book can be ordered at www.viewstodiefor.com.au

Discover more from Changing Sydney

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.