In his superb 2018 book River Dreams, Ian Tyrrell writes that the recent history of the Cooks River has been influenced through the prism of rejection.

Tyrrell notes that, in 1788, the British First Fleet’s Captain Arthur Phillip visited the waterway, with the benefit of a 1770 report from explorer Captain James Cook. However, Phillip rejected the Cooks River as a location for permanent settlement.

“The river was not the ‘fine stream’ that Cook apparently noticed, but a turgid and episodic thing almost undeserving of the title ‘river’ in European parlance,” Tyrrell writes.

“Mudflats and ‘swamps’ abounded, making the hinterland a disappointment too, not the ‘fine meadow’ that Cook imagined.”

It was this rejection philosophy, and a resulting viewpoint that the river and its tributaries needed to be improved, which then influenced almost everything which happened in the next 180 years.

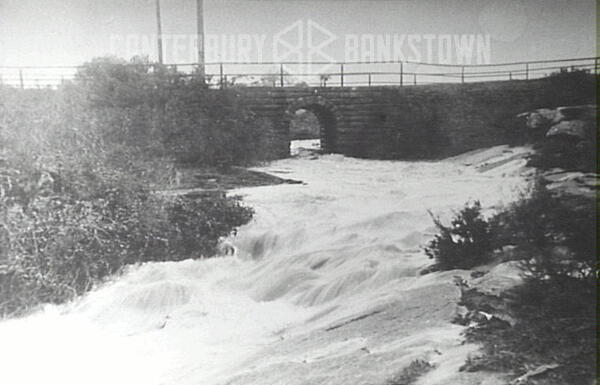

Dams were installed, wetlands were filled in and natural streams either turned into concrete channels, straightened or lined with steel sheeting.

The wetlands were filled in to develop land, but the resulting residential estates and industry created pollution of the worst kind, which was then left to fester in the river (including giant mounds of maggots) thanks to the blocking effect of the dams.

After the dams were removed, the concrete channels, straightening and sheeting were then largely designed to speed-up the river and its once graceful tributaries and streams to flush this pollution out to sea, rather than dealing with the real problem which was the pollution source.

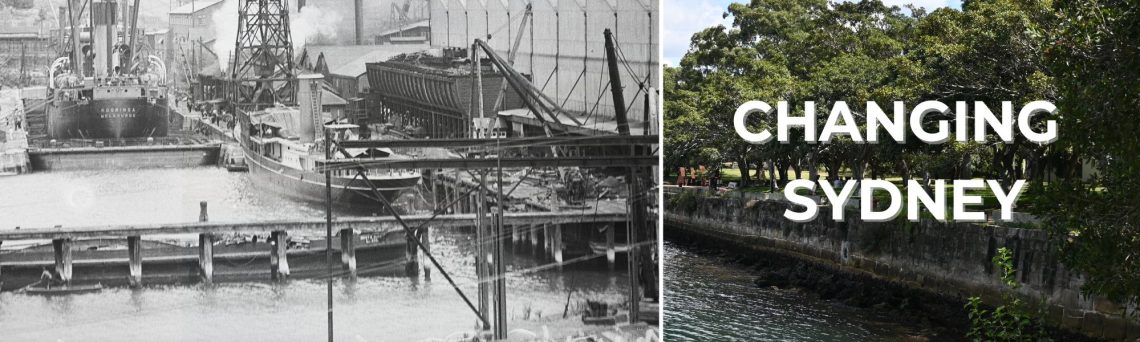

In addition, the river’s mouth was dramatically altered, over several stages, to construct an airport and in a failed attempt to build a Birmingham-style canal catering for industry and employment (Alexandra Canal).

Every intervention – every attempt at improvement – actually made things worse. The river was just fine as it was.

As a result, as Tyrrell writes, the Cooks River is now regarded as Australia’s most altered and polluted urban stream.

On Saturday, around 150 community members met at the Rowers on Cooks Club at Wolli Creek to discuss how to speed-up work to reverse some of these wrongs.

The event was titled “What’s making our river sick and how to fix it” and was organised by a coalition of river-focussed community and environmental groups, known as the Cooks River Community Collective.

The event primarily focussed on three issues – the steel sheeting, the concrete canalisation and the pollution source.

Long-standing Cooks River Mudcrabs co-ordinator Peter Munro explained that the steel sheet edging was installed from Hurlstone Park to Marrickville in the 1960s, as a cheaper alternative to concrete canals.

Some residents, he explained, can still remember the enormous and relentless pounding sounds as this sheeting was originally forced into the riverbanks.

He said the sheeting creates an ecological ‘no go’ zone, stopping the natural interactions between aquatic life and a riverbank, and also prevents humans from being able to access the river to kayak.

Even worse, and as can be clearly seen by walking along the river, this sheeting is now rusted and corroding in parts, making it both a new pollution source, a danger to people and an embarrassing eyesore. Munro said 1.43km of the sheeting could now be regarded as high risk, and 1.13km as medium risk.

Munro said that no NSW Government agency or council wanted to be responsible for the sheeting, despite the fact it was installed by the government.

He said recent discussions with the government indicated the current solution was to fence the sheeting, rather than fix the problem, a statement which drew groans from the audience.

Cooks River Valley Association committee member Gareth Wreford then spoke about the concrete canals. He said Sydney Water was responsible for 13.5km of concrete canals from Canterbury to Chullora and that, while some progress had been made to naturalise some sections of the river, more work needed to be done.

Wreford pointed to some recent good examples of naturalisation, both within the Cooks River catchment and overseas, as to how this could be done.

Water program assessment and evaluation manager Brian Keogh then spoke about the need to introduce water sensitive urban design controls into the assessment of new development.

He explained that this was needed to slow down the rate of water flowing from urban development and in doing this stop litter, sentiment and other pollution (including sewage from illegal stormwater connections) being flushed into the river.

He showed other examples of where this had been done, including in Sydney Park at St Peters where the lakes now contain water from urban run-off which is clean enough to drink.

Keogh explained that, unfortunately, the Cooks River is still impacted by high levels of sewage pollution and low oxygen levels, which is inhibiting its recovery.

The event finished with unanimous support for a resolution that “the NSW Government should lead the revitalisation of the Cooks River catchment by naturalising the steel and concrete riverbanks and legislating to improve the water quality”.

The event was an illuminating overview of the challenges still faced by a waterway which should be a source of pride, rather than shame.

It also illustrated the opportunities that exist for far-sighted local, State and Federal authorities, and politicians, to turn back the clock on decades of misguided attempts to improve something which just needed to be left alone.

Discover more from Changing Sydney

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.